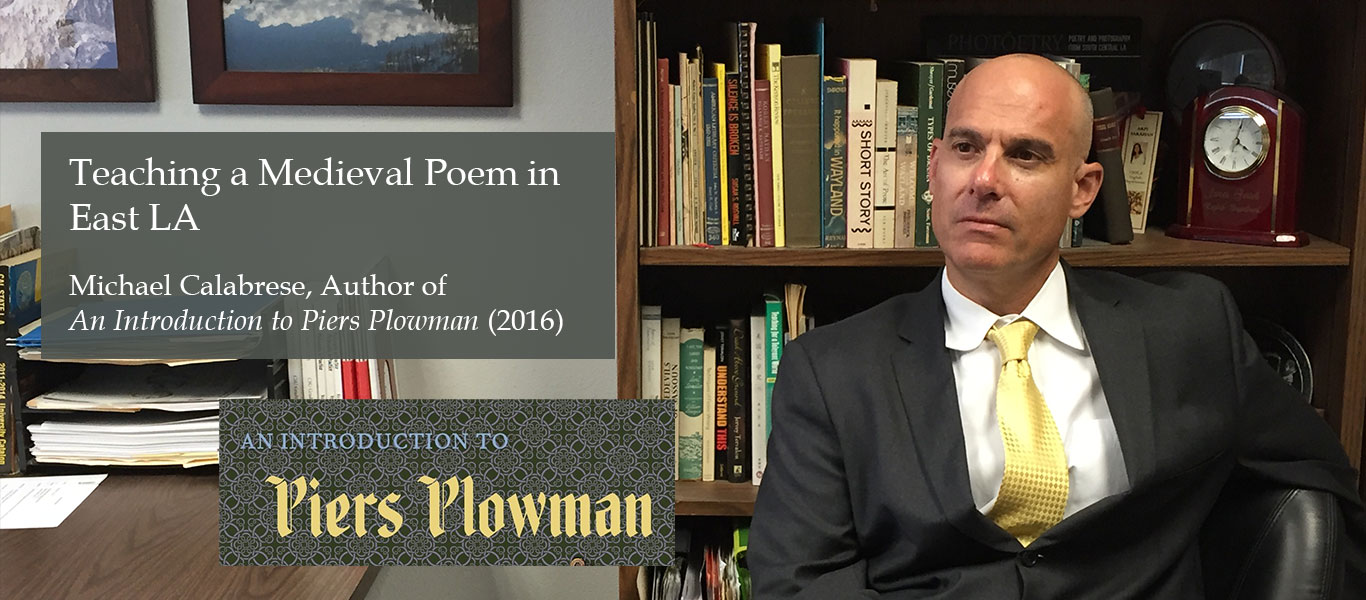

By Michael Calabrese

You’ve heard of Chaucer. But do you know Piers Plowman? Let me introduce this marvelous medieval epic: written by William Langland, Piers Plowman is a long allegorical poem from the late 14th century, chronicling the dreams and wanderings of a man named “Will”—the hungering human will, searching for truth in a corrupt world and materialist society. Will’s guide is “Piers (Peter) the Plowman,” a stern but loving man of the soil, who teaches Will the value of labor, both physical and spiritual.

Writing this guidebook for first-time readers of the poem, I was deeply influenced by my 22 years teaching at California State University, Los Angeles. CSULA is a designated Hispanic Serving Institution, and its bilingual population is a natural modern audience for a medieval poem that was originally composed in both English and Latin for a bilingual medieval readership. Medieval poets like Langland used Latin, most often from the Bible, to add both authority and spiritual doctrine to their poems, switching between languages depending on what needed to be expressed and how—a practice familiar to bilingual students.

Michael Calabrese (right) and medieval literature student Elsi Mendez (left).

Students from the Hispanic cultures of Southern California, with roots in the religious cultures of Mexico and Central America, often have direct experience with the living history of religious institutions and doctrines that are foundational to reading and understanding Piers Plowman. For instance, they know what friars are because of the twenty-one missions that friars built here, some of which are still the actual parishes my students attend.

This kind of teaching is important today because some people think—wrongly, I believe—that medieval European literature, British literature, canonical literature of any kind, belongs only to the “dominant” culture because it contains the histories of race, class, and gender oppressions that scholars today must unmask in the classroom and in criticism. To remedy this misconception we must provide all students with access to and ownership of a shared medieval past, and teaching poems like Piers Plowman helps us to do this.

Medieval language connects with my multicultural classroom. For example, long vowels in Middle English are not pronounced the same as in Modern English but sound more similar to medieval and modern Romance languages. Native speakers of Romance languages—like Spanish—read Middle English more accurately, including proper rolling of the r, than native English speakers do. In my classroom, Spanish speakers reciting the poem give native English speakers a unique opportunity to hear what Middle English literature may have originally sounded like. In my experience, both the medieval English and the powerful Latin that are laced dramatically through the verses find a linguistic, spiritual, and cultural home in the modern multicultural classroom, especially among bilingual readers. I have been so lucky to teach this demographic here in East LA.

Michael Calabrese and his students, engaged with class outside during a fire drill.

In terms of its themes and ideas, Piers Plowman is engaged with social politics, so it often excites students as it excited Langland’s original readers. The poem’s social relevance draws the reader into a seemingly alien medieval world and reveals, finally, that it is not alien at all. Teaching the poem in California, which has a formal holiday in honor of a modern-day Piers the Plowman, the union leader Cesar Chavez, adds local significance. But each classroom and reader engaging with the poem will feel the irresistible power of the noble, hardworking plowman fighting for truth and justice. We all love to root for such a hero, and we all appreciate the integrity of physical—and spiritual—labor.

Piers Plowman also confronts other issues—personal, theological, and civic—that all peoples and societies must struggle with. I am always amazed at how well the poem works in class and the way students apply it to a range of current economic and social topics. They particularly enjoy the great scene of the confession of the Seven Deadly Sins, an unsavory but funny troop of characters who regret—but not really—all their lying, stealing, hating and gluttony. (I believe that Shakespeare learned something about character and dramatic monologue from William Langland.)

Piers Plowman is by no means an old dead text. It resonates with students in my multicultural university classroom. It connects with as many contemporary debates and social justice issues as modern readers can think of, just as it did in its own time. It criticizes wealth, praises the poor, and speaks truth to power in ways that still appeal to us in modern society. It asks questions we still ask today in 2016, and I hope my book inspires readers to take up these eternal social, moral, and spiritual questions.