What is Coastal Archaeology?

Coastal archaeology deepens our understanding of how people lived in and interacted with coastal habitats and ecosystems across all continents throughout the history of our species. Coastlines hold special importance in many cultures as liminal spaces, bordering and marking the transitional boundaries between marine and terrestrial environments.

The Coastal Archaeology Lab facilitates collaborative local projects with California State Parks, Los Angeles County Natural History Museum, San Bernardino County Museum, and other organizations as well as collaborative binational projects in Baja California, Mexico. Students are engaged in a variety of thesis and research projects ranging from rock art studies to zooarchaeological analysis of historic faunal remains to archaeological shell studies and nearshore paleoenvironmental studies and helping prepare collections for repatriation.

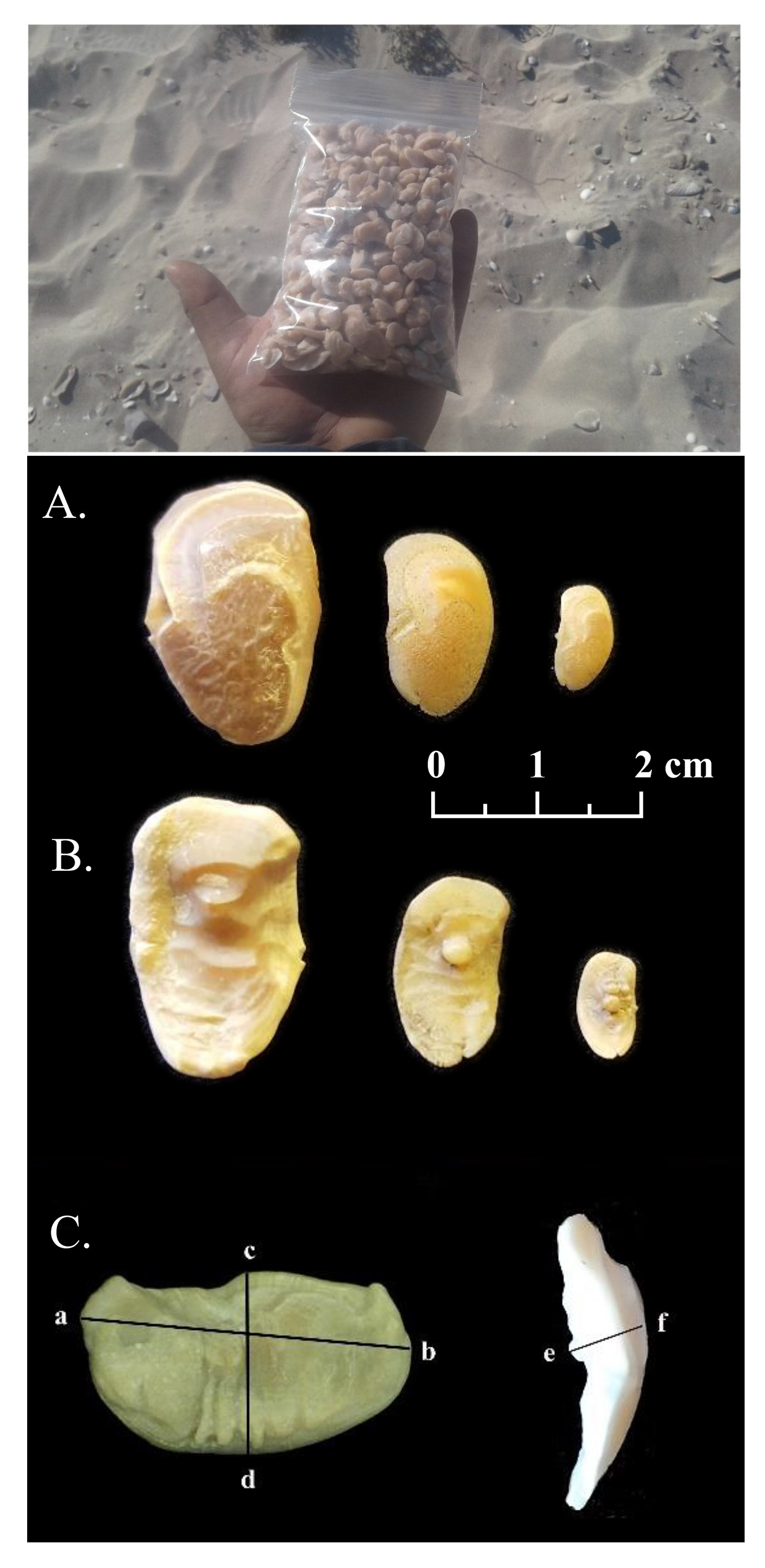

Coastal archaeology often falls under the realm of environmental archaeology as we employ archaeological shell studies to learn about human-environmental interactions, subsistence strategies and foodways, and many aspects of material culture including utilitarian implements, like tools and containers, ornaments, musical instruments, and even currency. Additionally, isotopic analyses and other analytical methods (i.e., sclerochronology) are increasingly being used to reconstruct and interpret paleoenvironmental records (i.e., paleo-sea surface temperature) and reconstruct the season of harvest and site occupation. Our lab facilities contain equipment to conduct sclerochronology studies, and to prep (etch and powder) shell and otoliths samples for 14C dating and stable isotope analysis.

On-Site Lab Equipment

- Buehler IsoMet Low Speed Saw

- Buehler EcoMet 30 Manual Grinder-Polisher

- Geomill326 precision milling machine

- Sherline Milling Machine

- Portable XRF

What Can We Learn from Studying Shells and Fish Bones?

Humans have altered and transformed the places we live for the entirety of our existence. Understanding the choices, impacts, and strategies of people in the past can help us make better choices today as we face numerous ongoing challenges including those of global climate change. Our research seeks to assist in this effort by using archaeological data to provide baseline information spanning hundreds or thousands of years for animal populations that have been severely impacted in recent decades.

Currently, fish are a major food source and primary economic pursuit along the upper Gulf of California, Mexico. Modern fisheries of the upper Gulf were severely impacted by sport and commercial fishing during the 20th century, depleting once-abundant stocks and pushing numerous endemic species to near extinction. In addition, anthropogenic impacts in the form of water diversion and damming of the Colorado River have turned the once hyper-productive upper Gulf estuary into a highly saline environment, negatively impacting the spawning cycles of many fish species and further hindering their recovery.

Archaeological evidence in the form of fish bones, otoliths, and shellfish show that people have been fishing and collecting shellfish along these coastlines for thousands of years, providing a wealth of baseline data and important historical context for modern fisheries. For example, our analysis of archaeological otoliths of Totoaba macdonaldii, which is currently Red List Endangered, reveals that people have been harvesting this huge fish (up to 2 meters in length and 200 pounds) for at least 6,000 years. In our study, morphometric measurements of otoliths, radiocarbon dating, and stable isotope analysis were used to describe the demographics of harvested populations, seasonality of fishing, and reconstruct aspects of the upper Gulf paleoenvironment during the past several thousand years.