It needs no introduction

In case you haven't heard, Cal State LA is converting from quarters to semesters. Starting in Fall 2016, we will no longer be on the quarter calendar (four equal academic terms per year), but on the semester calendar (two main terms, plus a shorter summer term and a very abbreviated winter "intersession"). The process of converting the campus has been, hmm, let's say complex, and the level of minutiae has only been matched by the impassioned arguments about minutiae, including why minutiae ought or ought not be spelled properly with a diphthong. If that word sounds smutty to you, I can only say that I am an English professor and fully qualified to use such language, though, as a nineteenth-century scholar not really qualified to discuss Latin.

But discuss them I do, as this series of emails archived on this page attest. In an effort to address concerns raised by faculty and staff about semester conversion, in the Spring of 2015 I wrote a series of emails (about one a week) that attempted to pull back the curtain on the process and on what shape our semester future might take. Egad! (yes, I actually wrote "Egad!") I think we better pull the curtain shut.

These musings are personal, were written hastily, and are probably marred by small errors that I intended to fix but didn't. The opinions and views expressed are solely those of the author or his team of hired ghost-writers. The contents of this page do not represent the views or opinions of the English Department, the College of Arts and Letters, California State University, Los Angeles, the California State University system, or the State of California, though they are probably shared by those who know that the angry core of incredulity and despair that lies at the heart of our skeptical engagement with the world is all that supports us in this our time of darkness.

And with that, Go, little emails, go, my little tragedy!

What They're Saying about Preparing for Semesters

"If I weren't dead, I'd sue him for plagiarism."

— Charles Dickens (deceased)

"You know nothing of my work. How you ever got to teach a course in anything is totally amazing."

— William Wordsworth

"I particularly enjoyed the soft chewy bits."

— John Wilson Croker

About the author

Jim Garrett is Professor of English and Chair of the English Department at Cal State LA. He specializes in British literature and culture of the nineteenth century, and is currently at work on this ridiculous page. He hopes to someday do other things, some of which are useful to others.

(April 6, 2015)

The University’s conversion to a semester calendar continues apace (or should that be athwart?). Virtually all courses and degree programs have been converted and approved and plans for advising the nearly 20,000 “transition” students are being developed. While I need to use the passive voice when speaking of the university (and I should probably put ironic quote marks around “plans” and “advising”), I don’t need the passive voice when it comes to the English Department. We really are developing plans for “transition advising,” which refers to advising those students who will have begun their degree programs under quarters but who won’t graduate until after we switch to semesters). One key goal of transition advising is reducing uncertainty and stress. This quarter we will be holding group advising and information sessions for majors and we are finalizing advisement guidelines and new forms (ah, now it’s official) as part of our effort to combat uncertainty.

Despite these efforts to assuage anxiety, we have been told to anticipate a rush for the door (or off the sinking ship?) as students, uneasy about the effect that semester conversion might have on their progress, attempt to graduate ASAP. To meet this anticipated need, the number of sections for majors next year has been increased by 8% over this year’s offerings and by nearly 15% when compared with 2013-2014. But as many of us have already experienced, the rush appears to have already started. Perhaps like Carlyle’s Herr Teufelsdrockh, we will be reduced to repeating to ourselves in the hallways three portentous syllables: Es geht an (It is beginning).

This anxiety about semester conversion when coupled with an increase in the number of English majors has produced significant demand for space in courses for English majors. Unfortunately, because the university now allows students to register for up to 16 units during the first phase of registration, latecomers found themselves shut out of classes. At this point in the term, the only option to accommodate this demand is to exceed enrollment limits, which is not so much an option as it is the proverbial gun to the head. Each instructor, of course, must balance compassion for students with the pedagogical effect of increasing class size. But, speaking departmentally (I do that sometimes), exceeding enrollment limits is not so much a slippery slope as a vertical decline.

Finally, while we are on the subject of assuaging (or creating) anxiety, I will be sending out a series of notes throughout the quarter under the subject “Preparing for Semesters . . .” These notes will hopefully combine the instructive with the agreeable, or, failing that high bar, combine in the Cal State LA way the not-completely incorrect with the not-totally disagreeable. I can promise that each missive will be less than 500 words, and therefore readable in under three minutes, which by the way is how long it probably took to read this one.

(April 8, 2015)

The other day I came across a poster board display my children had created for a geography project. Neatly printed on colored labels stuck on foam core were a series of “Fun Facts!” (exclamation point required), such as “Fun Fact! France is nearly as big as Texas.” Besides reminding me of the environmental guilt and trauma occasioned by school projects (foam core will likely outlast France), I was struck anew by the powerful conjunction of random and yet seemingly meaningful information that constitutes the “fun fact.” Only pure randomness or the irony of the universe could bring into agreement France and Texas.

Acknowledgement of randomness or irony is the best way to approach the class meeting times and academic calendar devised for semesters. In this note I begin on the new class meeting times (or “time blocks” to those of us “in the know”). For our department, the time blocks should be straightforward. Unlike departments that offer supervised instruction, labs, and activities, almost all of our courses are classified as lecture/discussion courses. For such courses one unit of course credit is equal to one “hour” of class time per week, where the CSU defines an “hour” as 50 minutes. Is it random, ironic, or just a fun fact that psychoanalysts also define an “hour” as 50 minutes?

When we move to semesters, virtually all of our courses will be three units and so will meet for 150 minutes each week. If the class meets once-a-week, then it will require a two-and-a-half hour time block. If it meets twice-a-week, then it will require two 75-minute time blocks. If it meets thrice-a-week, then it will require three 50-minute time blocks. “Thrice” probably caught your eye either because it made you wonder whether I’m wearing a bow-tie or because you were surprised (pleasantly or probably not so pleasantly) to learn that our longstanding Monday/Wednesday (MW) or Tuesday/Thursday (TR) class schedule might be changing when we move to semesters. In fact, three-unit semester courses will be required to be scheduled into either once-a-week two-and-a-half hour time blocks, twice-a-week 75-minute time blocks on TR, twice-a-week 75-minute time blocks on MW afternoons, or thrice-a-week 50 minute time blocks on Monday/Wednesday/Friday (MWF) mornings. If you need to create a chart or diagram to understand that last sentence, you are not alone. Besides the needless complexity, please also note the use of the passive voice.

It is still unclear how exactly departments will be “required” to schedule thrice-a-week MWF morning classes. When one of the senior administrators in charge of the campus’ semester conversion efforts was asked directly how these scheduling rules would be enforced, he raised his eyebrows, smiled, and said, “How are they being enforced now? Who’s enforcing them now?” In case you’re wondering, the answer to these questions is no one is enforcing class scheduling rules now, hence the use of the passive voice earlier. In other words, these scheduling requirements apparently are not requirements at all, but exactly how this understanding and other factors will affect how we schedule classes will have to wait until the next “Preparing for Semesters” note.

(April 13, 2015)

One of the more controversial aspects of semester conversion has been the class meeting times, specifically when the university announced that three-unit classes cannot be scheduled in twice-a-week 75-minute time blocks in the mornings on MW; instead classes formerly offered in the mornings on MW must be offered in 50-minute time blocks on MWF.

It turns out, though, that “cannot” and “must” might mean “should not” and “please,” or at least that was what a senior administrator implied when asked about the requirement to schedule MW morning classes as MWF morning classes. That moment, which occurred during one of those interminable meetings held in gray windowless conference rooms animated only by the hum of recycled air, was like Wordsworth’s encounter with the blind beggar—my mind turned as with the might of waters. The universe became momentarily elemental as the sham announced itself as such and my first response to suddenly seeing, as it were, the death’s head flashing beneath the human flesh, the randomness and emptiness revealed beneath the winking mask of knowingness, was despair over the loss of certainty. But in pure Nietzschean fashion, randomness and emptiness are merely imperfect understandings of irony and perfect freedom. As you can see, my mind wanders during these meetings in gray windowless conference rooms, (I thought Fifty Shades of Grey was the décor manual for the CSU), but if Blake can see the world in a grain of sand, then I can cling to the possibility of enlightenment in semester conversion.

Freedom can be its own uncertainty, but more on that later. Much actually is known about when classes will be scheduled. Once-a-week classes will mostly be scheduled in the evenings from 6:00pm-8:30pm, but it’s possible some might be scheduled during the day, either from 11:00am-1:30pm or 2:00pm-4:30pm. Twice-a-week classes in the mornings on Tuesday/Thursday (TR) will be scheduled in the following time blocks: 8:00am-9:15am, 9:30am-10:45am, and 11:00am-12:15pm. Twice-a-week classes in the afternoons on MW and TR will be scheduled in the following time blocks: 12:30pm-1:45pm, 2:00pm-3:15pm, and 4:00pm-5:15pm. Twice-a-week classes in the evenings on MW and TR will be scheduled from 6:00pm-7:15pm or 7:25pm-8:40pm. We probably won’t schedule many classes in the latter slot and it is even more unlikely we will use the last evening block from 8:50pm-10:05pm, though, that time might be perfect for a class on Gothic novels or a seminar on the Literary Cocktail (Gin Gimlets anyone?).

Besides the length of the class periods, a quick review of the new time blocks reveals other changes. The passing time between most classes will increase from ten to fifteen minutes. The afternoon “dead hour” (currently 3:15pm-4:15pm) will be replaced by two 45 minute breaks surrounding one 75-minute time block. It is unclear which programs and students are served by this strange late afternoon inefficiency where only one 75-minute class is scheduled in a nearly three-hour time block. (Apparently, the professional schools were very insistent about the scheduling necessary for the late afternoons and evenings.) And despite interest from some students in starting earlier (7:30am was proposed) and much interest from many students and instructors in starting later (8:30am was proposed), the university opted to stick with 8:00am as the first class meeting time.

Of course, that still leaves two key issues unresolved. How will the department decide between MW or MWF morning classes? And what about students? (“Who?” “Students.” “Students? I’m not following you.”) Do we know what they would prefer? In fact, we do know something about student preferences and what we know will help us at least partially answer the first question, when we return with the next installment of “Preparing for Semesters."

See Also

Simplified Semester Time Blocks for (Most) English Classes (/sites/default/files/groups/Department%20of%20English/q2s-engl-timeblocks_0.pdf)

Official University Semester Time Blocks (Very Complicated) (/sites/default/files/groups/Semester%20Conversion/time_modules/csula_time_modules_current.pdf)

(April 15, 2015)

Statistics. If your mind is already wandering, you probably want to skip this note, which is longer than the other notes by half and full of numbers and words like “measure” and “percentage.” But before you hit the delete key (or if you are using Wordstar, CTRL-Q, T), please read this executive summary: Students prefer classes early in the day, faculty prefer classes later in the day, and everybody wants a lunch break. If we can just manage to schedule everything between 11:00am and 12:30pm while also providing time for lunch, everybody will be happy. I hope it won’t come as too much of a surprise to learn that not everybody will be happy.

As part of its preparation for semesters, the English Department conducted a schedule preference survey of graduate students and undergraduate English majors. The undergraduate survey was sent to about 400 students and 75 responded (the first within six minutes—give that student an A!), for a response rate of nearly 20%. The graduate survey was sent to about 60 students and 25 responded, for a response rate of over 40%. The responses mostly confirmed past scheduling practices, but there were a few surprises.

In both surveys, students were presented with the semester time blocks and asked to mark each with “Most Prefer,” “Acceptable,” “Least Prefer,” or “No.” The undergraduate responses were relatively straightforward. Using the sum of the “Most Prefer” and “Acceptable” responses as a measure of popularity, the most popular time blocks for twice-a-week classes were 9:30am-10:45am (78%), 11:00am-12:15pm (77%), and 2:00pm-3:15pm (72%). Less popular were 12:30pm-1:45pm (59%), 4:00pm-5:15pm (55%), 8:00am-9:15am (51%), and 6:00pm-7:15pm (50%), and least popular was 7:25pm-8:40pm (38%). Another measure of preference is the percentage of “No” responses. By that measure the least popular time blocks were 8:00am-9:15am (32%), 12:30pm-1:45pm (31%), 7:25pm-8:40pm (30%), and 6:00pm-7:15pm (27%).

Besides mostly confirming existing student demand, these responses suggest that most students prefer a “school day” schedule with mornings most popular and classes ending by mid-afternoon. They also, apparently, want a lunch break. This desire for a “school day” schedule, perhaps, explains one somewhat surprising result: of all the time blocks the most popular for students were two thrice-a-week ones, 10:00am-10:50am (85%) and 11:00am-11:50am (82%). This result, combined with the 85% of respondents who characterized themselves as full-time students (12 or more units each term), confirms a longer-term demographic shift at CSULA to a more traditional college-age student population. Unfortunately, I neglected to ask respondents whether they preferred thrice-a-week, twice-a-week, or once-a-week classes, so it is unknown whether students actually prefer thrice-a-week classes or whether they were dutifully answering the survey questions resigned to the reality the survey purportedly reflected but was actually producing. (Who said Marxist theory was dead?)

The graduate student responses offered one surprise: possible interest in daytime seminar classes. Graduate students were only asked to indicate their preferred times for once-a-week classes, and they overwhelmingly preferred Monday-Thursday (MTWR) 6:00pm-8:45pm (88%). Less popular but popular nonetheless were MTWR 2:00pm-4:45pm (64%) and MTWR 11:00am-1:45pm (60%). Unpopular were the three Friday time blocks—12:00pm-2:45pm (36%), 4:00pm-6:40pm (40%), and 6:50pm-9:30pm (36%)—which, depending on your perspective, suggests either that today’s graduate students have lives or that they lack gumption.

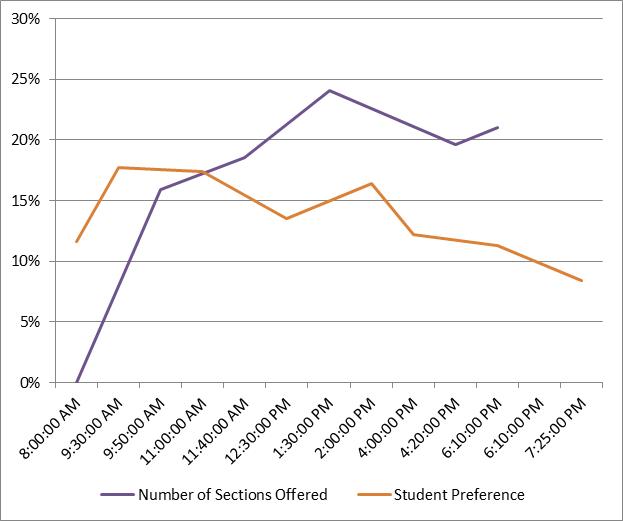

Of course, these percentages attached to time blocks are all relative. While the 51% of respondents who preferred 8:00am-9:15am might be low when compared to the 78% who preferred 9:30am-10:45am, 51% still indicates that more than half of all respondents marked 8:00am-9:15am as “Most Prefer” or “Acceptable.” In other words, some students actually prefer classes at 8:00am and 6:00pm, just not as many students as at other times. Interestingly, the department’s scheduling of classes for undergraduate majors has not always reflected these preferences. Over the last six years, for example, the department has not offered a single class for undergraduate majors at 8:00am. The reason, of course, is faculty preference, which enters into the determination of when courses are offered. (“Really?” you say as your monocle falls out.) The accompanying chart (if you can see it) shows this relationship by graphing the distribution of major course offerings throughout the day against the preferred times identified in the survey. While student demand peaks mid-morning and then tapers off throughout the day, the number of sections offered fails below student demand prior to 11:00am and exceeds student demand after 11:00am, peaking at mid-afternoon and tapering off slowly into evening. Or in short, undergraduate students prefer to take morning classes, while faculty prefer to teach afternoon classes. With insights like these, I could be a sociologist!

While the value given to student preference and faculty preference can be, um, negotiated when scheduling courses for the major, much less flexibility is possible when scheduling the department’s general education offerings. For these courses—which include first-year writing, general education literature and culture, and free electives open to students in any major—classes must be scheduled when students want to take them, which interestingly might not be determined by students, and will be the subject of our next installment.

See Also

Summary of Undergraduate Student Survey Results (on SurveyMonkey) (https://www.surveymonkey.com/results/SM-KR85RW67/)

Summary of Graduate Student Survey Results (on SurveyMonkey) (https://www.surveymonkey.com/results/SM-3HSQWW67/)

(April 22, 2015)

As noted in the last Preparing for Semesters note, most students favor a “school-day” schedule with morning classes preferred over afternoon and evening classes. That preference, though, hasn’t always been reflected in scheduling, except for writing and general education classes, where “market forces” (i.e., the student as consumer, course registration as the marketplace, general education as a buffet, the university as McDonald’s) purportedly play a more important role. The campus mandate that morning classes be scheduled either as thrice-a-week 50-minute classes on MWF or twice-a-week 75-minute classes on TTH will therefore have a significant effect on the scheduling of writing and general education classes and a lesser effect on the scheduling of major classes.

Taking the Winter 2015 quarter as typical, only two of the department’s 36 graduate and undergraduate major courses were scheduled on MW mornings, so the shift to MWF morning classes could have almost no effect on the scheduling of major and grad courses. Conversely, 43% of the department’s writing and general education course sections were scheduled on either MW or TR prior to 11:30am, and that percentage leaps to nearly 70% when the 11:40am classes are counted as part of the morning. For writing and GE, the shift from MW morning to MWF morning classes will be significant and will affect many in the department—of the 84 faculty members assigned classes in Winter 2015, 29 (or more than one-third) taught at least one MW class that started before 11:30am. Perhaps it goes without saying that faculty members who regularly teach writing and general education courses will need to prepare for the possibility of a teaching schedule that includes thrice-a-week 50-minute classes.

Before, however, you reserve a seat at the next CalPERS retirement planning workshop (CalPERS Planning Your Retirement), consider first how dark is the glass through which we are attempting to see. Invoking “market forces” and claiming that classes “must be scheduled when students want to take them” (as I did in the last note) might, for instance, suggest students have more agency than they have. The University has long toyed (verb chosen deliberately) with the idea of “block scheduling,” where first-year students do not choose their classes but are assigned them. Just last week, we learned that block scheduling is on hold for the immediate future (thus robbing me of the topic for this Preparing for Semesters note), but a host of other factors—such as space availability, the scheduling practices of other departments, and the bus schedules—create a much more complicated marketplace and leave students with something less than economic freedom.

And consider also the rich complexity reminiscent of Burton’s Anatomy of Melancholy found in the fine print of the Official University Semester Time Blocks (linked in the third note and below), which reads:

A minimum of 75% of each department’s undergraduate course sections must be offered within the currently approved, standard time blocks. For example, the current standard time module for day-time [sic] 3 semester unit classes is MWF for 50 minutes each day. However, under these revised guidelines, up to 25% of these sections can be offered on MW for 75 minutes each day. This applies to on-site and hybrid classes; classes meeting 100% online are exempted.

According to this administrative rule, up to 25% of a department’s course sections can be scheduled outside the “standard time blocks.” Note, however, the confusion introduced in the third sentence, where following the example of scheduling some MWF morning classes as MW morning classes, the phrase “up to 25% of these sections” suggests that this rule applies not to the total number of course sections offered by the department, but to some subset of the total. Aporia! What will we do with our moment of undecidability?

Besides affording deconstructive pleasure, the difference is significant. In Winter 2015, only 35 of the department’s 190 undergraduate course sections, or 18%, were scheduled on MW prior to 11:30am. If the rule is that up to 25% of all course sections can be scheduled outside the standard time blocks, then the department could schedule all of its MW morning offerings outside the standard time blocks. In other words, by this reckoning the department would not need to schedule any MWF course sections. If, however, the rule is up to 25% of MWF morning classes (for example), then, using the Winter 2015 schedule as an example, of the 35 MW morning classes the department would need to schedule at least 26 as MWF morning class.

Ultimately, as noted earlier, the decision does not belong solely to the university, the department, or to students, but to all parties working in good faith for mutual benefit. Some students will want to take MWF morning classes and some faculty will opt to teach them. How many? We don’t know. We will offer a mix of MW and MWF morning classes and let the imperfect market decide what it wants, while remaining nimble enough to respond methodically in the midst of the confusion that is likely to dawn on Monday, August 22, 2016, the first day of semester classes.

See Also

CalPERS Planning Your Retirement (https://www.calpers.ca.gov/index.jsp?bc=/member/education/education-center/classes/plan-retirement.xml)

Official University Semester Time Blocks (Very Complicated) (/sites/default/files/groups/Semester%20Conversion/time_modules/csula_time_modules_current.pdf)

(April 27, 2015)

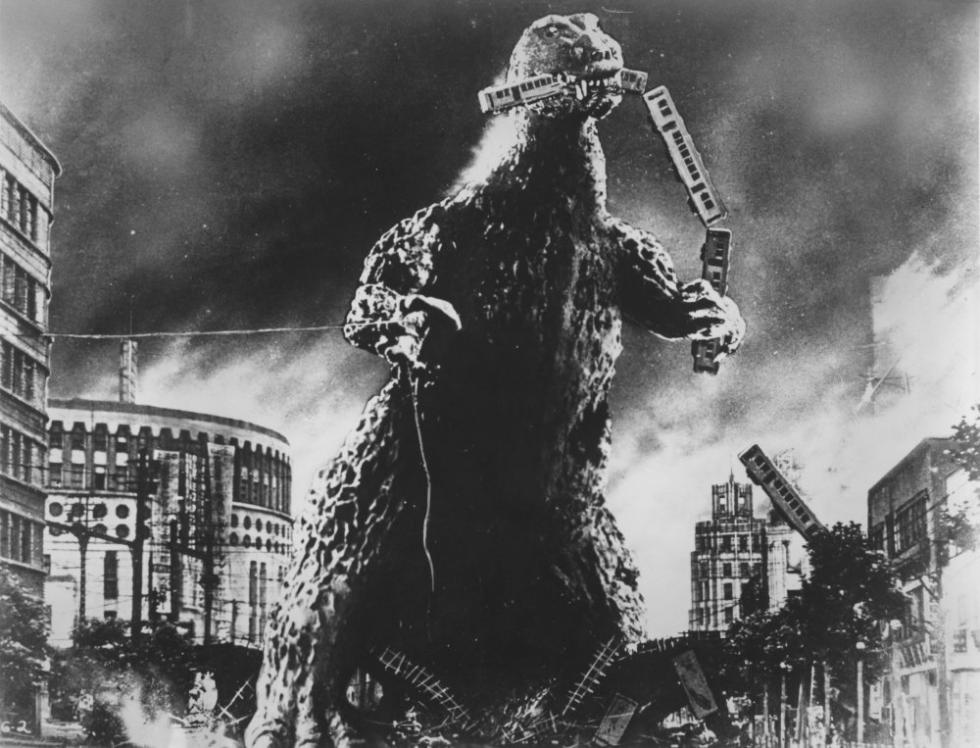

When semester classes begin at Cal State L.A., either all shall be well and all manner of thing shall be well, or many of us will be in fetal positions, rocking back and forth and muttering, “This is not happening. This is not happening. This is not happening.” It is happening and we even know when it start, Monday, August 22, 2016, a day that either will be like any other day or a day that will live in infamy. I’m hoping for the former, but planning on the latter, and I must admit that in thinking of this date my mind has been haunted by the vision of a 100-foot tall monster known cryptically as “Q2S” striding through the burning ruins of the university, fiendishly double-booking classrooms and getting indigestion from trying to eat the Administration building. Presumably, once past this slouching-towards-Bethlehem phase of semester conversion, or Phase Three as it is called in planning documents, we will begin to reap the benefits of converting to semesters. (Ironic? Even I can’t tell any more. Or as Schlegel asks, “What gods will save us from all these ironies?”)

But to proceed, the semester term adopted by the university will last sixteen weeks: fifteen weeks of instruction followed by an examination week. While the university elected not to include a “study week” prior to final exams (or “dead week” as some campuses call it), it did allocate one “study day” for each semester, where the campus would remain open but no classes would meet. Between the Fall and Spring semesters the university will offer a three-week long Winter intersession, not to be confused with a three-week long intercession, which ironically is what we will probably need around August 2016. The Summer term will be ten weeks long. During both the Winter intersession and the Summer term, classes will be offered through the campus’ College of Professional and Global Education (open university).

A look at the approved academic calendar for 2016-2017 shows how these new academic terms will be implemented in practice. The Fall semester will begin on Monday, August 22 and end on Saturday, December 10. The middle of October will be the halfway point of the semester, and Halloween will mark the beginning of the eleventh week, which on the quarter system would mean the end of the term (hooray!), but which on the semester system means “Hello November (and part of December).” The last day of instruction for Fall 2016 will be Monday, December 5 (to make up for the Monday lost to the Labor Day holiday), and final exams are scheduled for December 6-10. The Fall semester “study day” will be taken on Wednesday, November 23—the day before Thanksgiving—to create a two-day school week and a five-day weekend. How very French!

With finals week for the Fall 2016 semester ending on Saturday, December 10 and the Spring semester beginning on Monday, January 23, the winter break for most faculty will be six weeks long, or double the current winter break. (The university plans to offer some open university classes during the Winter intersession (scheduled for January 3-20, 2017), but it is very unlikely that we will offer any three-week long classes.) For most of us, the extra time will allow us to put off writing syllabi for six weeks instead of three.

The Spring semester begins on Monday, January 23 and ends on Saturday, May 13. For those of you unfamiliar with semester calendars, that’s right, May 13! The “study day” will be taken on Monday, May 15, with final exams scheduled for May 16-20. Spring Break is scheduled for March 20-25 (and is listed with initial caps on the university’s official calendar probably in preparation for a branding opportunity: “Cal State LA Spring Break brought to you by Meineke. We put the brakes on your Breaks.”) The break falls in the same week it would have fallen if we were still on the quarter calendar, and divides the semester into an eight-week first half and a seven-week second half. Because students will still have seven weeks of instruction after Spring Break, perhaps we will avoid the whimper that often characterizes the end of the academic year, sensed by students and faculty who like gathering swallows twittering in the sky are simultaneously present and already departing. That end comes on Saturday, May 20. The Summer 2017 term begins two weeks later and lasts for ten weeks from June 5 through August 12. After a one-week break in August, we start it all up again on Monday, August 21, 2017, for the 2017-2018 academic year.

See also

Pulp-O-Mizer: The Customizable Pulp Magazine Cover Generator (http://thrilling-tales.webomator.com/derange-o-lab/pulp-o-mizer/pulp-o-mizer.html)

John Keats, “To Autumn” (poets.org) (<http://www.poets.org/poetsorg/poem/autumn>)

(May 5, 2015)

[Caution: The following note continues the note bloat of the past few installments and will require five minutes or more to read.]

Like the campus as a whole, these notes on preparing for semesters have been more focused on time modules and calendars than on curriculum and students. (“Students?” Oh wait, I did that one already.) This tendency to become focused on the bottles and not on the wine points to the administrative mind’s essentially mechanical bent, where mechanical is used in the Coleridgean sense: to describe the uncreative tendency to impress “pre-determined form, not necessarily arising out of the properties of the material” on the inexhaustible world. Curriculum by this thinking is always polymorphic—ready to assume whatever shape we impose on it, or, to return to my metaphor, ready to take the shape of its container. And besides, as any fan of mixology (didn’t we used to call them drunks?) can tell you sometimes the bottles themselves really are interesting. As difficult as it might be, though, we need to turn our attention to the wine—and yes, you are free to turn that last clause into a refrigerator magnet.

While the rest of the campus shambles through semester conversion in a state of feverish lassitude (a favorite descriptor from Dickens, similar to Wordsworth’s “savage torpor”), the English Department is preparing to launch a restructured and expanded writing program, a host of new general education courses, and a more flexible and open undergraduate major. In this note we will focus on the writing program, treating the new GE courses and the modified undergraduate major later. (To learn more about the department’s semester writing courses, visit www.calstatela.edu/academic/english/semester-writing-courses.)

In the new writing program, students can satisfy the first-year writing requirement (GE A2) either by taking a two-semester first-year writing class (ENGL 1005AB, College Writing I and II, or “stretch” as it is sometimes called) or by taking a one-semester “accelerated” version of ENGL 1005AB. The two-semester first-year writing class, ENGL 1005A and 1005B, is intended for students who would prefer to stretch the curriculum of a first-year writing course across two terms rather than attempt the more challenging pace of the one-semester accelerated version (ENGL 1010, Accelerated College Writing). In time, through directed self-placement (DSP) all students will be permitted to choose either the two-semester or the one-semester course. For now (i.e., while we wait out the semester conversion bugs—think “Q2S” colossus astride the globe) we’re leaning towards requiring students who score 146 or below on the English Placement Test (EPT) to take the two-semester course (ENGL 1005AB). Students who either are exempt from the EPT or who score 147 or higher on the EPT will have the option of enrolling either in the two-semester or one-semester first-year writing course. Eventually, in that peaceful dawn of a new age into which we will all wake, all students will choose with guidance their first writing class. ENGL 1000, the one-unit supplemental writing workshop run through the University Writing Center, will be strongly recommended for all students attempting to take ENGL 1010 in the Fall term and all students attempting to take ENGL 1005B in the Spring. Eventually, ENGL 1000 will be included amongst the paths students can choose through DSP.

Moving to a stretch composition program for first-year writing eliminates the old pre-baccalaureate courses (ENGL 95 and 96) and even the idea of pre-baccalaureate courses in English, a move most other CSU campuses have either already made or are in the process of making. The impetus for the second big change in the writing program, though, came from outside the department. The new GE program folds the old university requirement for a second composition course (i.e., ENGL 102) into the standard 48-unit GE program. (I would say over my dead body, but here I am living and breathing, or well, at least breathing. Wait. Yes, I’m breathing.) The university requirement that students take a second course in written English composition will now be met by a course that combines critical thinking with instruction in writing. Our entry into this enrollment sweepstakes is ENGL 1050, Argumentative Writing and Critical Thinking, a course which integrates writing and other critical thinking activities to increase students’ learning while teaching them thinking skills for posing questions, proposing hypotheses, gathering and analyzing data, and making arguments, applicable to any discipline or interest. Or at least that’s what we said we would do in our course proposal. As anyone who has taught writing already knows, all writing classes are “critical thinking” classes already, but this new course will require a more intentional focus on the meta-language of critical thinking than possibly some of us would prefer. So now might be the time to brush up on your logical fallacies. Or is that kind of thinking just a red herring, or maybe a straw man, or a hasty generalization that will lead us to the slippery slope of making ad populam arguments?

The department will also be offering four elective courses in writing. These courses are of two kinds: general writing classes offering continued practice in writing; and technical and professional writing classes offering instruction and practice in workplace writing. The two general writing classes are ENGL 2010 and 3010. ENGL 2010, Intermediate College Writing, is a semester version of ENGL 102. ENGL 3010, Advanced College Writing, is an upper division elective designed to offer continued practice in writing with an emphasis on critical reading and writing and advanced rhetorical issues. Both courses will be promoted to departments and advisers as good electives for students needing additional practice and instruction in writing. Some departments (Economics and Finance so far) have already expressed interest in requiring their majors to take ENGL 3010. If there is sufficient interest, we might even offer college- or discipline-specific sections of this course.

The two professional and technical writing courses are ENGL 2030 and ENGL 3030. ENGL 2030, Introduction to Technical Writing, is a new course developed at the request of the College of Engineering, Computer Science, and Technology (ECST). All ECST majors will be required to take ENGL 2030, which means by 2017-2018 the English Department will need to accommodate up to 500 students each year. ENGL 3030, Professional and Technical Writing, focuses on methods of and practice in writing professional documents, reports, proposals, and other workplace writing. Like ENGL 3010, college- or discipline-specific sections of this course might be offered and departments and advisers will be encouraged to direct to this course students in need of further practice in writing.

See also

“Semester Writing Courses,” Cal State LA English Department (www.calstatela.edu/academic/english/semester-writing-courses)

(May 7, 2015)

We get mail. Steve Jones has offered several additions and corrections to earlier “Preparing for Semesters” notes, which I have chosen not to pass along out of concern that department faculty and staff already have so little to believe in. John Cleman has asked for permission to circulate these notes amongst emeriti faculty, I assume so that they can look back with renewed pleasure at the distance that separates them from our madness, or as Nietzsche might have said, “Better you than me.” Today, I would like to share with you an email I received from Kevin McCabe in response to my last note. Kevin, long-time lecturer and first-time note-writer, offers the following suggestion for a version of ENGL 1050, Argumentative Writing and Critical Thinking.

As a preemptive measure to avoid obsolescence, I would like to put in a course proposal for ENGL 1050: Argumentative Writing and Critical Thinking. While you mentioned some of the most fundamental logical fallacies at the bottom of the fourth paragraph of your recent "Preparing for Semesters" installment, you elided my favorite fallacy of all: the fallacy fallacy. Lest that term sounds illogical by dint of redundancy, the formally informal term is argumentum ad logicam. Basically, it posits that just because an argument is built on a fallacy, this does not obviate the soundness of an argument in of itself—hopefully, this does not interfere with my personal belief that if students italicize or bold the title of their papers, their essays are going to be atrocious and warrant no extraneous evaluation beyond their initial six (at most) centered, half-thought-out words.

Thus, I would like to propose for the Fall 2016 semester a couple sections of "ENGL 1050: A Fall of the Fallacy Fallacy." In essence, I will require my students to write arguments that are full of logical problems, and grade them on how well they failed to address the assigned essay prompt. This will be a refreshing break from my current situation, in which I ignore all of the logical holes, gasping and gaping throughout their essays, in order to assign them grades based upon how much time it took me to make sense of their essays.

Obviously, such a course will require relevant textbooks, thus I was thinking of assigning a deck of Tarot cards and the biography Reagan: A Life; I will utilize these sources to lead my students to a new logical fallacy: the fallacy fallacy fallacy. In analyzing this new type of fallacy, we will investigate the belief that assuming that a fallacy does not necessarily negate the legitimacy of an argument is a sort of retarded fallacy ("retarded" being used in the original denotative sense, not the common connotatively insensitive sense). At the end of Week 16, my students will be experts in the even newer logical aberration, The Trickle Down Fallacy, in which students wonder where the hell their tuition money went, at which point we will juxtapose the aforementioned fallacy with the Trickle Up Fallacy to truly expand their horizons, outward and beyond and sideways.

Ultimately, my goal is to pass my students into a new though-not-yet-accredited course, ENGL 1050X. Clearly, the "X" stands for "eXtra amazing," and the course title will be: "ENGL 1050X: The 'You-Think-You-Will-Have-a Job-After-All-of-This' Fallacy." As I am logically assuming that I will not, I hope that there will be a kinder, gentler minimum-wage earner to break such a harsh reality to our customers (oops, I meant to say "students," as they are definitely not "customers," unless one wants to get into my "The Customer is Always Right Fallacy," as detailed in my forthcoming "ENGL Mc1050: 'Would You Like to Supersize That?': The 'Words Super and Size are Not One Word' Rule").

Thanks Kevin.

As noted in the earlier discussion of the new semester writing courses, the campus also took the opportunity of semester conversion to revise its General Education (GE) program, a decision akin to volunteering for a colonscopy because you happened to be at the doctor’s office for a rash. Hmm. TMI. True, the campus had been engaged in conversations about GE, but conversation doesn’t necessarily produce consensus and going from talking about change to actually changing was done in the institutional equivalent of a heartbeat—a mere six or so months starting in September 2013. Almost more important than changing was the decision to “open up” GE. For years, parts of general education were “owned” by specific courses and departments and attempts to move into those territories were met with nothing less than gangland resistance. (And if you think the language is hyperbolic, ask the Psychology Department about their PTSD from attempting to propose a critical thinking course over a decade ago.) By linking the revision of GE with semester conversion and inviting all departments to propose new courses, all those old fiefdoms were cancelled in a moment and any department could, in theory, offer any course in any area. It was the triumph of learning outcomes over disciplinary expertise.

The opening up of GE coupled with over a decade moratorium on proposing new GE classes produced an overwhelming flood of new courses. Set to the rhythms of a Tom Lehrer song, the historians proposed to teach English, English proposed to teach history, and everyone proposed to teach critical thinking. This free-for-all was made even more precarious by the decision to eliminate the upper division themes, another area where certain courses and departments had held sway for years. The immediate consequence is a seeming boon to student choice. In 2013-2014, about 130 distinct courses were offered for lower division GE credit, and another 70 distinct courses were offered for upper division GE credit. At present, nearly 200 distinct courses have been approved for lower division GE credit and over 200 distinct courses have been approved for upper division GE credit. While enrollment has increased, it has not doubled or tripled as the number of GE courses has, suggesting that the first few years of semesters will witness a market shake-out as courses compete for enrollment. The “Money Matters” language is, of course, objectionable but apt to describe an educational enterprise turned over to this Friedmanesque (Milton or Marty? "That's Feldman not Friedman, you idiot") fantasy of the free market.

To market, to market we go! In keeping with the department’s long tradition of mixing sentimental optimism with hard-earned cynicism to form a curiously effective pragmatism, the department’s GE courses realize Horace’s profound advice to mix the “dulce” with the “utile,” or if you prefer your allusions to be slightly more contemporary, that a spoonful of sugar helps the medicine go down. (Yes, that’s my idea of contemporary.) Our existing GE offerings have been spruced and spiced up. (To see our semester GE offerings, visit /academic/english/semester-general-education-courses and to learn more about individual courses, click on the mini-banner image for the course.) In some cases, the changes are purely cosmetic. For example, our current course on mythology in literature (ENGL 258) has been rechristened “Gods, Monsters, and Heroes in World Mythology,” “Women and Literature” (ENGL 260) has been renamed “Fictions of Gender and Sexuality,” and the venerable “Understanding Literature” (ENGL 250) has been given a Churchillian urgency with its new name, “Why Literature Matters.” (Open with rumbling bass notes; cue Will Arnett voice-over.)

The additions to the department’s lower division GE offerings lean heavily towards the intersection between literature and the popular. Two courses on science fiction will be offered jointly with the Liberal Studies Department, and two of the other three new offerings even have the word “popular” in their titles. “Shakespeare and Popular Culture” is a lower division GE arts elective that explores the continued afterlives of Shakespeare’s plays especially in contemporary culture. “Popular Literature and Pulp Fictions” is a lower division GE humanities elective that focuses on popular genre fiction. Both courses, by theorizing the popular, will provide students with a critical perspective on their own tastes and values, and a theoretical basis for their aesthetic and economic choices. The third new lower division course is “Literary Los Angeles,” which will provide us with a much-needed opportunity to engage with our own literary histories and neighborhoods while helping students connect to their city. All of these new courses also place (or re-establish) pleasure at the center of reading and many of our lower division GE offerings make plain their investment in nurturing and supporting a culture of lifelong reading.

The additions to the department’s upper division GE offerings open up topics of great contemporary public interest as well as subjects of both historical and contemporary scholarship. “Psychology in Fairy Tales and Fantasy Literature” examines classic and contemporary literature from the perspective of understanding human motives, actions, and behaviors. “Money and Meaning” explores classic and contemporary literature in relation to economics, both in terms of its representation in text through production, exchange, circulation, greed, and debt (to name a few tropes) and in terms of its effect on literary production, circulation, and consumption. “The Body in Literature and Culture” examines the social construction of the human body and its position as site of both aesthetic pleasure and social power in texts and contexts ranging from the ancient to the contemporary. And “Crimes, Scenes, Interpretations: Literature and the Law” (get it?) focuses on the depiction of crime and punishment in literary texts and the concomitant enduring moral concerns of fairness, justice, right, and wrong such depictions raise from across historical periods and cultural contexts.

Whether the topic of the course is world mythology or contemporary representations of the human body, echoing through all of the departments’ arts and humanities GE courses is, I believe, the phrase “sapere aude!” [date to be wise]. I came across that phrase in Schiller (who must have been quoting someone else, because he was German, you know), and that intertextual moment—quoting a text written over two hundred years ago that was in turn quoting some unnamed text written perhaps two thousand years ago—realizes the primary goal of arts and humanities general education: to explore the diversity and complexity of the human search for meaning, value, and purpose. Or in the words of the new university, by monetizing these aspirationals we can close the loop on our low-hanging fruit and ideate our 360 strategy.

See Also

English Department’s Semester GE Courses (/academic/english/semester-general-education-courses)

Business Buzzword Generator at the Wall Street Journal (http://projects.wsj.com/buzzwords2014/)

As significant as the changes were to the writing program and to the department’s general education offerings, changes in the undergraduate major to take effect in Fall 2016 might in the long run prove more substantial. Long contemplated, discussed, reflected upon, debated, and the occasion of (egad!) more than one department retreat (including one (only one?) reminiscent of the most uncomfortable moments of Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?), the new undergraduate degree program creates a carefully scaffolded mix of small discussion-based seminars, tutorials, and practicums (or does Martin insist on ‘practica’?), large-lecture surveys, and mid-sized lecture-discussion electives. The introduction to the major tutorial workshop and the senior seminar or practicum offer hands-on intensive work on reading, thinking, and writing. The six required large-lecture “Core Readings” courses provide all majors with advanced introductions to the central components of a comprehensive English studies program and prepare students to take more focused and advanced senior-level electives. The mid-sized senior-level electives permit majors to develop a single focus or multiple foci, aided perhaps by taking multiple electives in one or more of the ten designated focus areas.

Once undergraduate majors have completed their general education writing courses (ENGL 1005AB or ENGL 1010 and ENGL 1050), they are eligible to enroll in ENGL 2900, English Tutorial. The tutorial experience, innovative and yet ancient (let’s call it paleopedagogical), provides the backbone of the program’s emphasis on developing the habits of mind—self-reflection, skepticism, patience, openness to uncertainty—essential to creative and critical humanistic thought. Based on the Oxford tutorial system where a small group of students meets weekly with a faculty member to discuss readings and student work, these small group experiences permit students to work closely, collaboratively, and intensively with faculty on reading, thinking, and writing. Sorry, no sherry will be served except on special occasions, like Tuesdays. ENGL 2900 is pre- or co-requisite to the “Core Readings” courses, which introduce majors to the concepts, histories, and theories central to the study of literature and language, and thus serve as “gateway” courses to 4000-level electives. The six Core Readings courses cover language and linguistics (ENGL 3100), theory (ENGL 3200), ancient and medieval literature (ENGL 3300), British literature since the Renaissance (ENGL 3400), American literature (ENGL 3600), and modern and contemporary world literature (ENGL 3700). Wireless microphones and i>clickers will soon be competing with my attempt to explain Kant’s “purposiveness without a purpose” for the what-went-wrong-during-today’s-lecture prize. Each of these Core Readings courses, in turn, will serve as pre- or co-requisite to more advanced and focused 4000-level electives. For example, to enroll in ENGL 4406, The Romantic Age, students must have completed ENGL 2900 (English Tutorial) and either have completed or be concurrently enrolled in ENGL 3400 (Readings in British Literature).

In the old program, coverage of the broad range of concepts, theories, histories, and traditions that comprise English Studies was achieved by mandating specific numbers of courses in specific areas: three courses in American literature, two courses in linguistics, two courses in world literature, and so on. The new program achieves comprehensive coverage through the Core Readings courses, which provide concentrated introductions to key sub-disciplines in the study of language and literature. One key consequence of shifting the burden of coverage and breadth to 3000-level survey courses is that nearly half of the units for General Option undergraduate majors can be used for electives in the new program, compared to the maximum 20% electives available in the current program. But before that wide expanse of electives gets you thinking that students unmoored by strict course requirements will fill their program with courses on absurd topics like David Beckham or management ethics, the department has developed focus areas to help students concentrate their electives on areas of interest or to achieve specific post-graduate goals. These focus areas are optional advising guides that will provide students with lists of courses with common foci. So far, the department has created ten focus areas, including theory and culture, writing studies, preparation for graduate study in English, language and linguistics, and several literature areas.

Near the end of their undergraduate careers, students will take a senior seminar, choosing between one focused on research in language and literature and practicums focused either on practical application or teaching. Again the basic pedagogic model is very traditional, the seminar (with its slightly awkward (or more so) etymology) being one of the oldest forms of institutional instruction and the practicum adapting an apprenticeship model, but the courses themselves promise to be innovative. (Sorry for the traces of hype in this repurposed text.) Finally, all majors will complete a one-unit Senior Capstone, which will offer an opportunity for senior English majors to review and better understand the major issues, themes, theories and research findings in the field of English, and reflect on how they might use and further develop their knowledge, whether in their future career or advanced academic endeavors, or as lifelong learners and cultural contributors.

As these notes have probably made all too clear, some things are changing around here over the next few years, and while at least the curricular changes have been thoughtful and self-willed, we, like educational institutions everywhere and at all levels, are suffering from “change fatigue,” which is so severe it threatens to collapse the distinction between the change that is a necessary component of intellectual and institutional growth and change that feels like chasing the latest bright shiny new thing. Or maybe it isn’t even latest, bright, shiny, or even new. It doesn’t help that the purveyors of bright shiny new things are not only most often in charge, but are also almost always graduates of the Blanche DuBois School of Management, their reforms relying entirely on the kindness (and free labor) of strangers. From talk about change to actually changing; that time is nearly upon us. Last Monday, for the first time in nearly a year, the Educational Policy Committee had no converted courses to consider. All the paperwork has been filed and in our case an ambitious slate of courses and programs has been approved. Now we just have to build the thing, a topic that will be the subject of our last few Preparing for Semesters notes.

See Also

Core Courses for English Majors (/academic/english/core-classes-english-majors) (this link was supposed to be attached to the last Preparing for Semesters)

Much energy, passion, and intelligence (well, energy and passion certainly) has gone into debates over the new general education program, the time modules for semester classes, and the academic calendar for the post-apocalypse campus. Did I say apocalypse? That’s odd; I meant to say conversion, of course. Nearly lost in the tongue-wagging, finger pointing, backslapping, and eye rolling (feel free to add your own body idioms) is the question some of us are most anxious about: how will the longer term and shorter periods affect our teaching? Academic governance nearly broke down over whether undergraduates ought to take one or two labs or how diverse “diversity” courses should be, questions that might affect only 5% of a student’s college credits, but a conversation about what might be involved in transforming 100-minute classes into 75 or 50 minutes and ten-week schedules into fifteen has yet to occur, giving credence, perhaps, to the pejorative use of the adjective “academic.” Or maybe most faculty are relatively unconcerned about the changes in the schedule. “Teaching is teaching,” they might say as they put their shoulders to the wheel, which, if you know your Groucho, means we will all soon be flat on our backs again presumably run over by that wheel.

I subscribe to both opinions, feeling considerable uncertainty about the change in tempo from the allegro con brio of quarters to the andante misterioso of semesters (from Groucho to Mahler in two sentences!), and yet knowing full well that we are constantly making adjustments in space and time and that ultimately “teaching is teaching.” With an eye towards understanding better how the change in the calendar will affect my teaching and with some desire to anticipate the rhythm of the semester, the next few “Preparing for Semesters” notes will present some of the logistical questions I have encountered in thinking about how to convert some of my existing courses to semesters.

I started with a first-year writing class, not because it is easier to plan, but because it has been the subject of several hallway conversations just in the last couple of weeks. Before I can sketch out a schedule for a writing class, I need to know how many significant (or formal) writing projects will be assigned and whether the final assessment will include a portfolio. Once those two questions are settled, the rest is relatively straightforward. The approved course proposal for the first-year writing course (ENGL 1010) specifies that students will complete “at least four formal essays of at least 1,000 words each.” While the course outlined in the approved course proposal does not require a portfolio, for the sake of this exercise I am assuming four writing projects (the minimum required but also a common number for a semester-length first-year writing class) and an end-of-the-term portfolio. I also am assuming twice-a-week class meetings under both quarters and semesters simply because it simplifies the following discussion.

In looking over my syllabi for writing classes I discovered that on the quarter calendar, each writing project tended to occupy parts of six class meetings: two or three class meetings to work on understanding the readings, to discuss possible topics, brainstorm, and engage in other invention and pre-writing activities, and to begin drafting; one or two class meetings for draft workshops and peer review; and one or two class meetings for revision activities. To fit four writing projects into twenty class meetings, the end of one writing project had to overlap the start of the next writing project—the same class meeting might be devoted partially to peer review and revision work on the first essay and reading discussion and invention preparatory to the second essay. For each writing project then a student might have less than three weeks between when they start preparing to write (reading due) to when they were expected to hand in a revised draft. On the semester calendar, to fit four writing projects into thirty class meetings, one would probably continue the practice of overlapping the end of one project with the beginning of the next project. The key difference is that each project would have eight or nine class meetings: three or four class meetings to work on understanding the readings, etc.; two class meetings for draft workshops and peer review; and two class meetings for revision activities. This increase in the number of class meetings devoted to each writing project is not an increase in class time, but it is an increase in calendar time. Six 100-minute class sessions is essentially equal to eight 75-minute class sessions, but three weeks is not equal to four weeks.

To put this difference into perspective we can compare an ENGL 101 class offered in Fall 2015 to an ENGL 1010 class offered in Fall 2016. Both classes require four formal writing projects (really, that’s what it says in the course outline). In quarters, to fit four formal assignments into a ten-week schedule, each project needs to fit into a three-week block, with the last week of each project also doubling as the first week of the next project. The result is each project (reading, planning/inventing, drafting, revising, editing) occupies parts of six class meetings with 16-19 days elapsing from the date the first reading assignment is due to the date the revised essay is due. For example, in the course schedule I mocked up for this note, students might be expected to start discussing the reading for the second essay at the start of the third week of the quarter (October 12 for a MW class in Fall 2015). A rough draft for some kind of peer review activity might then be due on October 21, with a final revised draft due on October 28, the end of the fifth week. In semesters, to fit four formal assignments into a fifteen-week schedule, each project can be allowed four or more weeks, again with the last week of each project doubling as the first week of the next project. Each project (reading, planning/inventing, drafting, revising, editing) occupies parts of eight class meetings, with 26-28 days elapsing from the date the first reading assignment is due to the date the revised essay is due. Using the Fall 2016 calendar, for example, students might be expected to start discussing the reading for the second essay at the end of the fourth week of the semester (September 14 for a MW class in Fall 2016). A rough draft for peer review might be due on either September 28 or October 3, with a final revised draft due on October 10, the start of the eighth week.

Many of our faculty have recent (or even concurrent) experience with semesters and undoubtedly have much more thoughtful approaches and insights to offer than the above rough sketches and rude stonework. I hope over the next year, we will have many opportunities to share our experiences (i.e., exploit their knowledge) and offer each other help (i.e., work for free). With our shoulders to the wheel, in no time at all we should all be flat on our backs again.

See also

Professor Quincy Adams Wagstaff Engages in Strategic Planning (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xHash5takWU)

In the last Preparing for Semesters note I attempted to model the process of converting a class from quarters to semesters. I focused on a writing class because doing so allowed me to think in terms of multi-week projects (i.e. essay assignments) instead of daily readings and activities and thus avoid the somewhat frightening prospect of trying to determine the relationship between our present 100-minute time blocks and our new 50- and 75-minute time blocks. In this Preparing for Semesters note, I offer my own experiences in trying to convert from quarters to semesters two courses that I regularly teach: ENGL 446B, The British Novel: Nineteenth Century; and ENGL 467, The Romantic Age. I started with the course on the 19th century British novel and in about a day I had completely ruined the course and was forced to abandon the attempt in gleeful despair—gleeful because I had created a great course containing both Bleak House and Middlemarch, and despair because I had created a ridiculous course containing both Bleak House and Middlemarch. Converting the course on British Romanticism was a much easier and more successful process, because of the two lessons I learned in botching the earlier conversion attempt. Like dinner table rules for children, the lessons are obvious, but nearly impossible to implement. First, don’t use the “additional” days in the semester calendar to add to the reading list, and second, use the “failures” of the current quarter-version of a course to create a better semester course.

I have taught ENGL 446B eight times and after several years of assigning too much reading and issuing multiple “revised” syllabi throughout the quarter, the course has settled in the last couple of years into a very effective (if I may say so myself) and popular course. The reading list usually consists of six or seven novels, ranging from short popular genre fiction that can be read in a few hours (H. G. Wells’ The Time Machine, for example) to Victorian novels that require a considerably greater investment of time and energy, such as George Eliot’s Middlemarch. Each quarter I change the reading list a little to amuse myself, but it usually takes the following form: Austen or one of the Brontës or Gaskell, Dickens, Eliot, some genre fiction (Doyle, Stevenson, Wells, for example), and Hardy. When I taught the course in Winter 2015, the reading list was Persuasion, Hard Times, Middlemarch, The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, The Sign of Four, and Jude the Obscure. To simulate the experience of Victorian readers, Middlemarch was read in parts across eight weeks of the quarter with the other readings read alongside it. For example, in week 4, students were assigned to read Book 2 of Middlemarch for Tuesday, and the first volume (12 chapters) of Hard Times for Thursday.

When I turned to converting ENGL 446B to semesters, I started with a copy of my syllabus from Winter 2015. My first step was to add in the additional class meetings for semesters. The Tuesday/Thursday Winter quarter class with 20 class meetings became a Tuesday/Thursday Spring 2017 semester class with thirty class meetings. The course schedule in my syllabus is formatted as a table, so after every two rows in the old (quarter-based) schedule I inserted a blank row. I then changed all the days of the week and dates to match the Spring 2017 calendar, leaving me with a schedule with ten blank days to fill. [First mistake: the “added” days are not in addition; and the “blank days” do not need to be filled.] My first thought was Middlemarch. In looking at the Spring 2017 calendar I noticed that the semester was cut in half by the Spring Break. Because Middlemarch is a late Victorian novel, it made no sense to read it in the first half of the semester, so I put it in the second half. [Second mistake: thinking in terms of weeks hides the fact that the class meeting time is shorter each week.] Because the second half was only seven weeks, I had to double up on the reading at the beginning of the second half of the semester, which I thought would be no problem since students would be coming back from Spring Break and therefore I could certainly expect them to do some substantial reading of Eliot over the break. [Third mistake: do I really think students will spend their break reading anything for school, let alone Middlemarch?] The rest of the second half of the term would parallel the quarter-based courses: Middlemarch alternating with short popular fiction and then with a Hardy novel. [Fourth mistake: still thinking in terms of weeks.] Moving Middlemarch to the second half of the semester also opened up a huge blank in the first half (eight weeks) of the semester, which now only had Austen’s Persuasion and Dickens’ Hard Times. Huge blank equals opportunity for more assigned reading. [At this point, the Q2S monster is holding a train over its head.] I decided to create a similar serial reading experience in the first half and swapped Hard Times (the completely uncharacteristic Dickens novel that serves as the compromise text in countless 19th century novel courses) for a “real” Dickens’ novel, like David Copperfield or Bleak House. Having recently taught Bleak House, I put it in the schedule, each week assigning about three monthly parts, but just in case I also started re-reading David Copperfield (no, David, Steerforth will not steer you forth!). With Bleak House spread across seven weeks (the first week of the term devoted to introductions and background), Persuasions could be read alongside it for two weeks, leaving three to four weeks available for another book, such as Jane Eyre, which like so many three-volume novels of the 19th century is well-suited to being split across three weeks. [Cut to silhouette of adults and children holding hands as they survey the smoking ruins of Los Angeles.]

It is probably obvious what went wrong in converting ENGL 446B from quarters to semesters: charming though self-defeating exuberance. Knowing that a three-unit semester course was the same as a four-unit quarter course did not prevent me from seeing the “blank days” in the calendar as new and unused and therefore available for additional materials. In the quarter-based course, students were assigned about 250-300 pages of fiction a week, the six novels totaling about 2,200 pages. In the semester-based course, students were assigned about 250-300 pages of fiction a week, the seven novels totaling about 3,100 pages. But a week in the quarter system is not the same as a week in the semester system. In planning our classes, we assume two hours of outside work for every hour of class time. For a four-unit quarter-based course, students should expect to spend eight hours each week preparing for class. While on the heavy side, 250-300 pages of reading each week for a four-unit quarter class is not unreasonable. For a three-unit semester course, however, students can be expected to spend only six hours a week preparing for class, which means that in the semester version of this 19th century novel class, the weekly assigned reading should not have exceeded 180-225 pages. In short, in converting an existing course to semesters, the “contents” of the ten-week course should be stretched across the fifteen-week semester. The days “added” to the schedule are not “new,” “empty,” or “blank” days waiting to be filled. How then should I decide what to do with these “added” days in the schedule? That question and one possible answer will be the subject of the next and last Preparing for Semesters note.

In attempting to convert a course I commonly teach on the 19th century British novel, I succumbed to the lure of the Japanese lunch buffet: if one serving of mystery sushi is good, two or even three servings must be great. The result was predictable for the course and the sushi and the less said about both the better. For instructors like me who are always despairing over what didn’t fit into the course, the conversion to the semester calendar can look like an all-you-can-eat buffet. The lesson learned in this first attempt to convert a literature course to semesters was that the days “added” to the schedule are not “new,” “empty,” or “blank” days waiting to be filled with fabulous readings left out of prior versions of the course only as compromises to Time’s winged chariot. (Did you ever wonder what sound a winged chariot makes? And isn’t Time a jerk? When I hear Time at my back, I slow down.) Instead, in converting an existing course to semesters, the “contents” of the ten-week course should be stretched across the fifteen-week semester. To quote a great Jedi master and personal friend, “Patience you must have, my young padawan.”

Equipped with the wisdom won through failure, I attempted to convert another class I regularly teach, ENGL 467, The Romantic Age. I have taught this upper division course on British Romanticism once every year since I joined the faculty at Cal State L.A. It is primarily a poetry course. Poetry makes up the assigned readings for half of the class meetings, and some poetry is included in the assigned readings for 16 of the 20 class meetings. As before, I started with a copy of a recent syllabus and added in the additional class meetings for semesters. The Monday/Wednesday quarter class with 20 class meetings became a Monday/Wednesday Fall 2016 semester class with thirty class meetings. Since the course schedule in my syllabus is formatted as a table, I again simply inserted an extra row after every two rows in the old (quarter-based) schedule and then changed all the days of the week and dates to match the Fall 2016 calendar.

Again as before, the new schedule had ten “blank” days to fill, but instead of immediately adding Don Juan to the schedule (it’s 16,000 lines by the way) I started with a question: what current reading assignments need more time? What always feels rushed? Keats’ odes and Coleridge’s The Rime of the Ancient Mariner came immediately to mind. Byron, who in recent years has been reduced to one day, has been sorely neglected. The sublime, The Prelude, Lyrical Ballads, John Clare. Blake always needs more time. In short, it took but a few moments thought to fill up the blank spaces in the schedule without adding any new readings. Multiple selections formerly scheduled on one day (Burke, Paine, Barbauld, and Burns all addressing issues raised by the French Revolution) were split across two. One particularly ridiculous day’s reading assignment was split across three days, which in consequence allowed one day for Blake’s Songs of Innocence and one day for his Songs of Experience. Two days on Keats’ odes and two days on Coleridge’s Rime of the Ancient Mariner were easy additions to the schedule given my desire (and tendency) to spend an entire class period on one Keats poem. Without adding a single text to the schedule, eight of the ten “added” days were filled. And with two days left over, maybe we can read Don Juan.

In truth, this narrative I have just told of initial failure followed by triumph, while appealing to my own narrative desires, didn’t actually happen. When I first thought of using my own experience as a kind of experiment in conversion (sounds like a Thomas Hooker tract), I naturally turned to my British Romanticism class first. I “successfully” converted the class, first by adding ten days into the schedule (as I did above) and then filling those added days with neglected readings: Equiano’s “Interesting Narrative,” Wordsworth’s “Michael,” more selections from Wordsworth’s Prelude, another canto from Byron’s Don Juan, Shelley’s “Mont Blanc” and “Hymn to Intellectual Beauty,” and so forth. I then turned my attention to the 19th century British novel course and was awakened into the experience and wisdom described in the previous Preparing for Semesters note. That failure made me realize that I needed to return to the British Romanticism course and start over, and it is that second attempt that is described above. Maybe art really does improve reality, or as Alvy Singer says at the end of Annie Hall, “Whaddya want? It was my first play.”

One of our themes has been that much is still uncertain and unknown and one of our goals has been to wade into that uncertainty and know it. My sense is that converting courses is the easy part because this is what we know. What we don’t know could fill a dozen of these lengthy emails (or thirteen to be exact). One other thing I know is that Time’s winged chariot is drawing near. What a jerk! Maybe I’ll pull over and let him pass.