SPRING 2015 / A BRAVE STRUGGLE

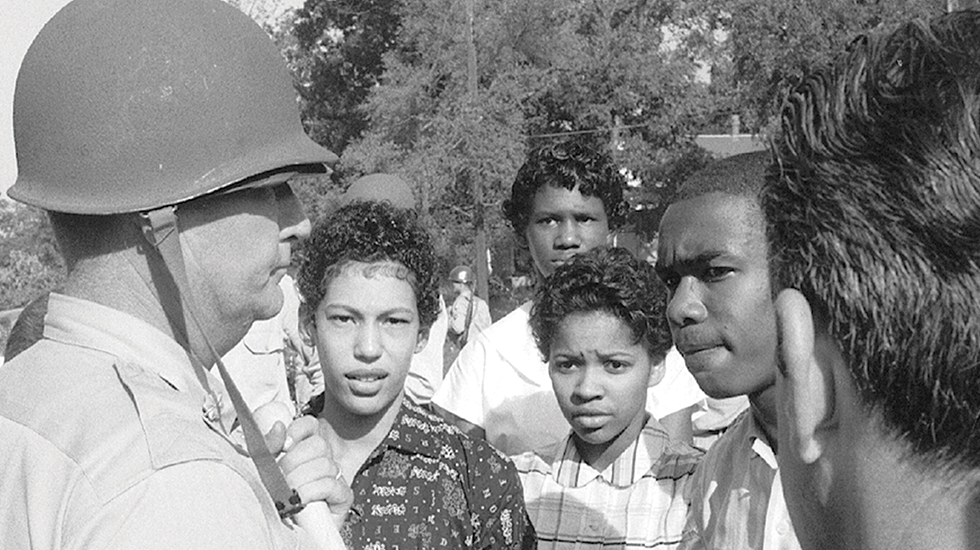

Arkansas National Guard and students - September 1957

A Brave Struggle

The lives of Sylvia Mendez ('76) and Terrence Roberts ('67)

have followed parallel paths. Both are Cal State L.A. alumni.

Both worked in the helping professions.

Both learned—early in life—what it means to fight for

change that leads to social justice.

INTERVIEW BY JOCELYN Y. STEWART

In 1947, Mendez was a central figure in Mendez v. Westminster, the landmark court case that led to the desegregation of schools in California. Roberts was one of the Little Rock Nine, a group of teenagers who integrated Central High School in Arkansas in 1957, three years after Brown v. Board of Education declared segregated schools unconstitutional nationwide.

Cal State L.A. Today’s Jocelyn Stewart sat down with Mendez and Roberts to discuss their lives and the roles they played in the fight against segregation.

Today: What made your parents decide to take a stand?

Mendez: My parents Gonzalo and Felicitas Mendez decided to fight when I was denied entry into a white school. I think that my father was so upset because he had met discrimination here in California many times. But that was just such a blatant form of discrimination. I was being denied entry to a school that was right next to my home. And [school officials] wanted me to go to a school that was ten blocks away or farther away.

Felicitas and Gonzalo Mendez (Photo courtesy Sylvia Mendez)

Roberts: I came home…and told [my parents] that I had volunteered to become one of the first kids to integrate Central High School. Without hesitation they said we will support your decision one hundred percent...They were stalwart in their efforts to put themselves as a buffer between me and all of the madness that ensued, because we were targeted viciously by the folk who were in opposition.

Today: Talk to us about the repercussions your families faced because of their decision to integrate the schools.

Mendez: [My father] was being called a communist at the time because he was trying to fight the establishment and people didn’t want to join him there in the neighborhood. They were comfortable in the segregated school in Westminster. They weren’t aware of what was going on. Some of the parents were so complacent.

Roberts: We were the objects of drive-bys, which basically meant that we had to be on guard for dynamite, or shotgun blasts or rocks thrown through windows, hate mail, phone calls 24-7.

Today: At the time did you understand the historical significance of the events in which you were involved?

Mendez: I truly did not understand the significance at the time I was denied entry into that school. I was 8 years old and all I could think of was wanting to go to that beautiful school. It had manicured lawns, a wonderful playground. They had monkey bars. They had swings.

As a child Sylvia Mendez integrated an elementary school in Orange County. (Photo courtesy Sylvia Mendez)

Roberts: I did understand the historical significance of what was going on because at the time I was involved, I was 15 years old and entering the 11th grade and I’d had the benefit of having been exposed to a cadre of very well-informed teachers at the all-black school who were angry about the fact that they were relegated to that job. They couldn’t get jobs in their professions. They were trained in various and sundry professions, but they couldn’t get jobs. They could teach in the all-black schools. As a consequence of understanding that their anger, if allowed to take over, would make it impossible for them to function themselves, let alone teach us, they harnessed that anger and put it into driving us toward excellence.

The Little Rock Nine and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People’s Daisy Bates. Terrence Roberts is standing, third from the left. (Photo courtesy Library of Congress/NAACP)

Today: Take us back to the first day of school.

[Mendez v. Westminster was appealed. During the appeal the Mendez family moved to Santa Ana and Mendez’s parents refused to send their children to the segregated school.]

Mendez: I’m in that white school in Santa Ana. The school bell rings and I go out to play and this little white boy comes up to me and he says, you’re a Mexican, what are you doing here? Don’t you know Mexicans aren’t allowed to go to this white school? Why are you here? And I started crying…I go home and I say, ‘Mother I don’t want to go to that white school. They don’t want us in that white school.’ My mother says, “Sylvia, don’t you realize why you were in court every day? Don’t you know what we were fighting for while we were in court?” I said, ‘yes to get into that white school with that beautiful playground.’ She said, “No, Sylvia. We were fighting for you because you’re just as good as that little white boy. Because under God we’re all equal….of course you’re going to go back to school.” And of course I went back to school.

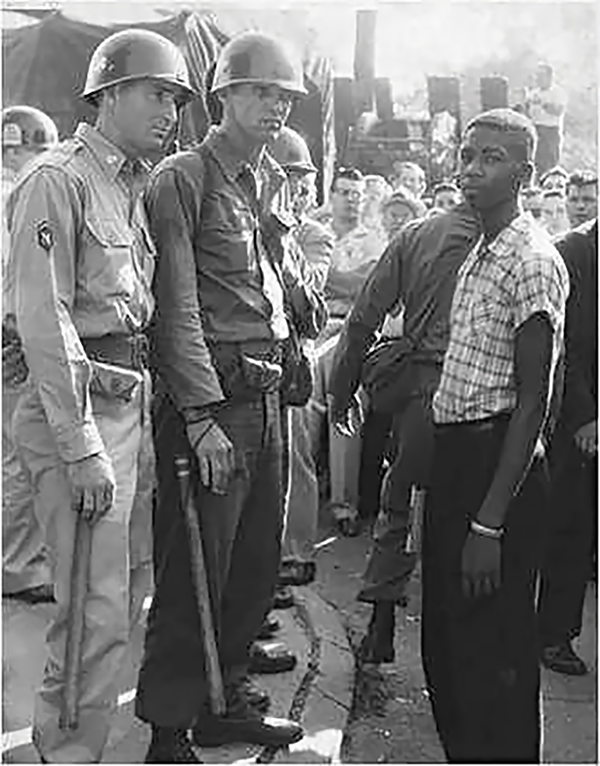

A 15-year-old Terrence Roberts is turned away from Central High School by members of the National Guard. (Photo courtesy Central High School Museum Historical Collections/UALR Archives)

Roberts: The very first day, when the nine of us attempted to enter the school, we were not allowed to enter because the National Guard was there to keep us out. The governor of the state of Arkansas had determined that the only way to prevent desegregation was to bring out the National Guard. So we were not able to cross those lines. We left, it took some court wrangling, some confrontations with authorities and so forth, and finally the governor relented, took away the National Guard and then we attempted to get back into the school---this time under the protection of the Little Rock police force, which was a big mistake...We were in school less than two hours before the mob broke through the lines and we had to be spirited out through an underground garage and a couple of squad cars to escape the mob’s violence. That was time two. The third time...we had the 101st Airborne Division of the U.S. Army taking us to school. And even though we had the army with us, that didn’t mean that the mob violence stopped. In fact, that only incensed them more...We went through that entire year with armed guards escorting us from class to class.

Today: Tell us what happened after that first year, and then bring us up to Cal State L.A.

[In response to integration efforts, the governor of Arkansas ordered schools closed for the 1958-59 school year. Roberts moved to Los Angeles and lived with an aunt and uncle while he attended Los Angeles High School. He earned a bachelor’s degree in sociology from Cal State L.A., a master’s degree from UCLA, and a Ph.D. from Southern Illinois University, Carbondale. Roberts later ran a psychology practice.]

Roberts, third from the right, and other members of the Little Rock Nine watch as President Bill Clinton signs a bill making Little Rock Central High School a National Historic Site in 1998. Roberts received the Congressional Gold Medal in 1999. (Photo courtesy of William J. Clinton Presidential Library)

Roberts: I think the part that Cal State L.A. played was that…they were very close; I didn’t have to go far to get here. And they provided me opportunities to have classes at the time that I needed them, because I was a working student….I worked from 10 [p.m.] at night to 6 a.m. in the mornings, then I had an 8 o’clock class here at Cal State.

[Mendez became a registered nurse. She later earned a bachelor’s degree at Cal State L.A.]

Mendez: It was beautiful because I was working at the hospital full-time. I worked from 3 a.m. to 11 a.m., so I could spend all day here at the college...So while I was a supervisor there, I could still be a student here. And that’s how I was able to get my bachelor’s here and then become assistant nursing director…at the pediatric pavilion at L.A. County USC Medical Center.

Mendez was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2011. (Photo courtesy of Getty Images)

Today: What is the primary lesson you’d like students to take away from your story?

Mendez: I want them to know how lucky they are that they are able to come to Cal State L.A. or whatever university they desire, because that’s what’s going to give them a wonderful, comfortable future in whatever career they decide to go into.

Roberts: Cal State L.A. offers a preparation, if you will, a crucible in which students can prepare themselves for life. But there has to be active involvement in that process….It’s important for students to have some sense of priority to become, as my first grade teacher said to me, ‘become the executive in charge of your own learning.’…then you can go out and do in life what you are put on this planet to do.